James Nicholls revisits Lake Dumbleyung, Australia, where Donald Campbell broke both the land and water speed records in the same year

Much has been written about Donald Campbell’s final world water speed record attempt, which ended so tragically on January 4, 1967 when Bluebird K7 backflipped into oblivion on Coniston Water, but the Englishman’s previous attempts at the record have faded largely into obscurity.

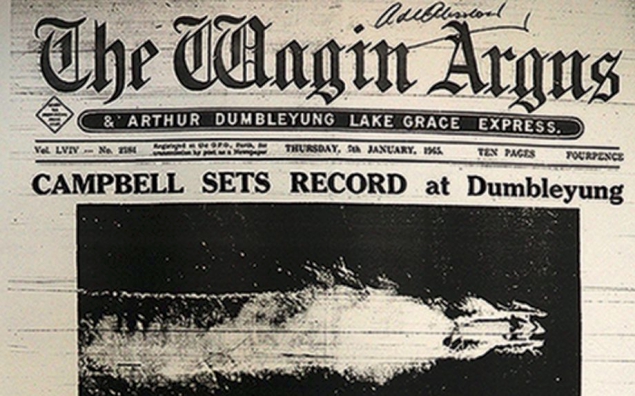

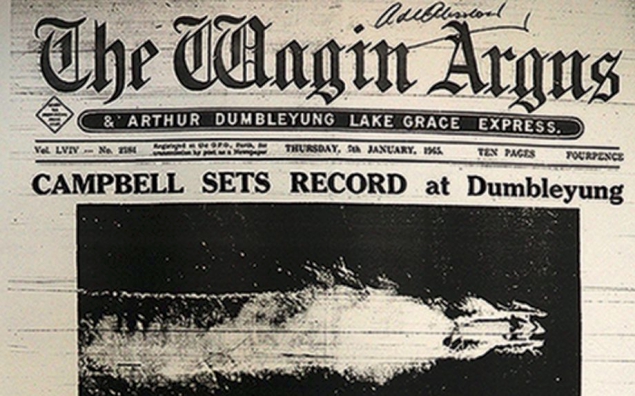

Arguably the most remarkable of these occurred at Lake Dumbleyung in Western Australia in December 1964. Having already set a world land speed record of 403.1mph in his Bluebird CN7 car on the dried-out Lake Eyre in South Australia five months earlier, Campbell set out to do something which nobody had ever done before – break the land and water speed records in the same year.

The fact that he already held the world water speed record, which he had increased each year in 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958 and 1959 to a peak of 260.35mph, did not deter him one iota. If he succeeded in setting new land and water speed records in the same calendar year, something that even his famous father Sir Malcolm Campbell had never achieved, then surely this would deliver him the acclaim and recognition he so desperately sought.

Donald Campbell felt he lived in the shadow of his father’s record-breaking feats, which had earned him a knighthood and worldwide acclaim in the bleak post-war years. Even though Donald had achieved similar success and was now the first man to pilot a wheel-driven car at over 400mph on the treacherous surface of Lake Eyre, he still felt the need to prove himself.

But times were a-changing and in the age of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, moon rockets and jet planes, Donald Campbell’s feats of bravery didn’t seem to capture the British public’s imagination in quite the same way.

In Australia at least, after his torrid yet ultimately successful time in Lake Eyre, he was still a hero. And it was here that he planned to pull off the impossible. Initially, he took his Bluebird K7 to another lake in South Australia – Lake Bonney at Barmera – for a September attempt at a new world water speed record.

As at Lake Eyre, Campbell’s early runs were beset by problems. The weather refused to play ball with consistent high winds ruffling the surface and, if truth be told, Lake Bonney probably wasn’t large enough for the kind of speeds he was aiming for. Even when the wind wasn’t blowing, continuous currents unsettled the surface of the water.

Despite the dangers, on November 23 he managed to get Bluebird K7 up to 216mph, which although well short of his Lake Coniston world record of ’59, was a new Australian record. With time running out he decided to relocate to a different stretch of water, Lake Dumbleyung in the heart of Western Australia’s wheat belt some 1,600 miles to the west.

So the long journey and the logistical nightmare of finding transport, accommodation and press support began once again, in a place that the regional tourist board still describes as: “Out of the way. Out of this world.”

Donald Campbell’s challenge begins

Having been to Lake Eyre to research a story on Campbell’s land speed record attempt, I felt compelled to follow in his footsteps to Lake Dumbleyung to discover what the arrival of his entourage and the media circus that followed would have been like all those years ago.

Lake Dumbleyung is set among a patchwork of fields full of golden wheat and grazing sheep. The small surrounding towns are miles apart and date back to the 1880s. It is beautiful countryside reminiscent of Kent, but on a much grander scale with fields the size of English counties and roads where I drove for an hour without seeing another living soul.

Even in the 21st century this region can be an intimidating place often with nothing to keep you company other than the omnipresent blood-sucking march flies and a temperature in December that rarely drops below 33°C. Having said that, after the stress of Lake Eyre and the disappointment of Lake Bonney, it must have been a pleasure for Donald Campbell, and his depleted retinue, though still including his wife Tonia and engineer Leo Villa, to arrive at Lake Dumbleyung.

The lake is 13km long and at its widest 6.5km across but in the 19th and early 20th century this salt-water lake was often without much water, much as it is today. But in 1964 heavy rains meant the lake was full to brimming. It was perfect, as long as the wind did not blow and the local duck population stayed away.

Fifty years on and having already experienced all the ennui, heat, frustration and flies that Lake Eyre had to offer, I too found myself at Lake Dumbleyung. I was hoping to talk to people who remembered what had taken place on this lake so far from anywhere.

If you want to stay at Dumbleyung, then there is still only one option: the Dumbleyung Tavern. It was here that Donald Campbell spent Christmas 1964, and it was to here that I had been directed for a meeting with the landlord Ian McCormack, who recalled in detail the impression that Campbell and his boat had made on him half a century ago.

“I was nearly eight years of age but of course when you get such a significant event occur in your life, even at that age, you do remember. The other thing that probably assists that memory is that my mother and father were passionate about it. Dad was the local policeman and involved with all the comings and goings. And of course as little kids we sort of hung around and listened to everybody.”

One of his father’s jobs was to try and rid the lake of shell ducks prior to each record run, by doing high-speed runs with the ski boats, but the memory which still burns longest is that of Campbell’s final record attempt.

“I remember going out to the lake early in the morning of December 31,” says Ian. “Donald’s major dream was to do what he called the double – the land speed record and the water speed record in the same calendar year. Now it was the last day of the year. There was only one more chance and that was it, today.

“He’d been trying for, what, eight, nine, ten days or so to break the record but conditions hadn’t been correct, so now we’re left with just one day and it was going to be hot, very hot. The wind was blowing a gale and the lake had waves on it, 12, 15, 18 inches high.

“Around midday or thereabouts Donald had sort of given up the ghost and thought right-o, well we’re going to fly to Perth. He’d been invited to various New Year’s Eve parties and stuff, so I think he figured he might as well go and enjoy them, so he left the camp to go and fly his own aircraft to Perth. But as he took off, I guess out of natural curiosity or whatever, he looked at the lake and saw that the surface was getting calmer. He did a very steep turn over the lake and came straight back in to land.

“Around three o’clock they were ready to go, people were in position and the conditions were classified perfect – no wind, ideal conditions, flat lake. We were standing right there, watched it all, the boat going back into the water and then the run itself. There weren’t a lot of people there; I’ve been told there were only 21 people actually at base camp. Even as kids we knew that this was his last chance to do the double.”

In the nick of time

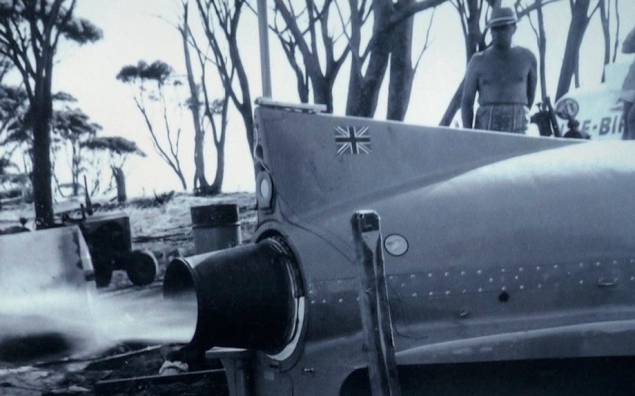

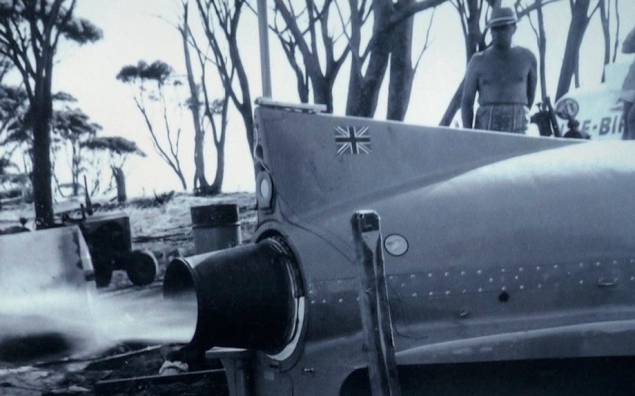

Ian took me to the little known spot where ‘base camp’ had been, where they whiled away the hours in the searing heat waiting for the right conditions. You can still see where the tree stumps had been removed and a ditch dug so that Bluebird could be slipped into the shallow water. Bluebird K7 was an extraordinary craft.

Designed by brothers Ken and Lew Norris and first launched at Ullswater in February 1955 it had gone through various iterations by the time of the Lake Dumbleyung attempt. At 8.05 metres long, 3.20 metres wide and weighing over 2 tonnes, with its Metro-Vickers ‘Beryl’ turbojet engine, which at full throttle could drain its 51 gallon fuel tank in under four minutes, it was quite a beast to drag to the other side of the world.

I’d heard rumours that Donald Campbell wasn’t wearing his race suit on the first of his two timed runs and Ian is quick to confirm them. “Donald didn’t wear his driving suit, he simply didn’t have time. As I say, this was all a rush, a big rush. He did take his helmet, that’s proven by photos, but I can confirm that he did not take his mascot (a soft toy called Mr Whoppet).

“I was standing right near Tonia and she was holding Mr Whoppet. The first and only time, as far as I’m aware, that he’d ever done a run in his boat or car without his mascot.”

It’s a good job Donald Campbell never noticed that his lucky mascot was missing or he might have had second thoughts about undertaking the runs at all. As it is he fired up the jet engine and roared off into the distance before turning round and repeating it in the other direction within the stipulated one-hour period.

“When Bluebird came in to shore, we were all very, very excited,” recalls Ian. We knew they had trouble with the timing gear. The official speed couldn’t be verified immediately, but it looked like there would be a new record, we just didn’t know exactly what the figures were. Tonia was so excited that she ended up jumping in the water and swimming out to the boat.”

Only once they’d gone back to the pub to calculate the figures did the team announce a new world record. He’d done it. The double was his. On his last attempt on the last day of the year, Donald Campbell had set a new world water speed record of 276.33mph, becoming the only person ever to break the land and water speed records in the same calendar year.

Just two years and four days later the swashbuckling Donald Campbell would die at the wheel of Bluebird K7 as he attempted to raise the record once more on Lake Coniston. It’s a testament to his achievements that his record has only been bettered three times since, the last occasion in 1978 when Australian Ken Warby set a new record of 317.60mph at Blowering Dam in New South Wales.

The final thing I’m shown in Dumbleyung is a letter dated February 27, 1967 from Leo Villa, faithful chief engineer to both Malcolm and Donald, who replied to a letter of condolence from the land owner who had granted access to Lake Dumbleyung. Villa wrote: “Please convey my regards to the kind people of Dumbleyung who strived so hard with Donald to achieve our last record in 1964”.

First published in the July 2015 issue of Motor Boat & Yachting.